The United States is a nation of immigrants. Chances are that either you are an immigrant or you know somebody who is one. Even if you’re not an immigrant yourself, you can still relate to this article because it’s about transitions. What are they? How do you manage them? I’d like to share my story about how I came to this country, and the challenges I faced in the process.

It was November of the year 2000 and I was excited to come to the United States from my native Venezuela. My mother’s mother had already been here for 30-plus years living in Andover, Mass., with her American husband, my step-grandfather Joseph. I was looking forward to the opportunity to enroll at UMass-Boston, to learning, working, and making a living here. I wanted to be able to walk safely without fear of getting mugged, in a place where a woman can wear whatever she wants without worrying that someone may want to rob you because your necklace is too pretty.

Although it is still a Third-World nation, I come from a country that was also a safe haven for immigrants at one time. Both of my paternal grandparents came to Venezuela from abroad before World War II. My paternal grandpa was from Asturias, Spain, and grandma came from Larache, Morocco. They made their home and continued to grow their family in Venezuela and it seemed to them like paradise back then. Only four percent of the population lived in poverty. The economy was great until 1983 when Viernes Negro (Black Friday) happened and the Venezuelan currency suffered such a severe devaluation that soon 26 percent of the population was living below the poverty line.

My Paternal Grandparents: Ramon and Maruja

Today, about half the population that is left in Venezuela (because so many people have left during the past two decades) lives below the poverty line. It’s a country run by a former bus driver with no political experience, and not much education. The current president never went to college and I’m not sure he even finished high school. He recently declared that government employees would only work two days a week. The social, economic, and political situation has continued in a long and messy, downward spiral.

At some point, I decided to look to the United States for new and better opportunities. I was ready to try to make the first major transition I had to face in my life.

Anatomy of Transitions

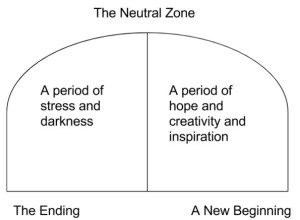

What is considered a major transition? Any significant change in life like a graduation, getting married, buying a house, having children, losing loved ones, moving to a new country, are good examples. The changes can be wanted or unwanted. It doesn’t matter. The adjustment is traumatic either way. Transitions start with an ending, go through a neutral zone and end with a new beginning. A version of what happened to me is explained in the book: Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes by William Bridges.

The initial excitement of being here was soon worn away by a number of things: by the headaches I would get when I had to switch from speaking in Spanish at home in Somerville, Mass. with my Venezuelan roommates, to speaking English at school for class and for work, by the long hours of school, followed by work, followed by tutoring, by no longer being able to spend my holidays with my siblings and parents, by missing the Venezuelan food I’ve always loved, and by no longer having perfect weather almost all year round. It started to hit me: I’m not on vacation. My life in Venezuela is over. I live here now.

My New Beginning

It wasn’t easy for me to be homesick, but thanks to the support of my parents and friends, I knew a light would be waiting at the end of the tunnel. So, I pushed through the neutral zone, I graduated from college and got a full-time job. I stopped tutoring so I had more time to do fun tourism in and around the amazing city of Boston. And I began to save money to be able to visit my family for the holidays. I also learned that it is better to have the right layers of wool in the winter rather than wearing six layers of cotton clothes. I also found ingredients at the supermarket to make Venezuelan food, and Latin American restaurants that made me feel like I was home, even just for a meal.

I have now been in the United States for a long time. I became a U.S. Citizen in August of 2007. I no longer feel Venezuelan because I can’t relate to the idiosyncrasies of that country anymore. Nor do I feel fully American yet. I am still getting used to idiomatic expressions in English, and odd things like why Americans abuse acronyms. As the musician Sting says in a song: “I’m an alien. I’m a legal alien.”

I have been through many other major transitions since I moved to the US: I got divorced and then found love again and remarried. I bought a house (talk about stress!). My husband started his own practice from home (he’s a therapist). And recently I began working at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Immigrating to this country helped me to become better equipped to understand the transitions that would come later in life, but I am still learning. It isn’t always easy. But, my friends and family will always be there to support me and that is what matters most. I wish you luck in your own future transitions. Just remember: A new beginning always waits just beyond the neutral zone.

I saw a timely article that relates to the situation in Venezuela. Check it out:The Pain of Watching Your Country Fall Apart http://www.huffingtonpost.com/alfredo-j-ramirez/the-pain-of-watching-your-country-fall-apart_b_9852388.html

Wow, I had no idea the situation was this bad “Every single friend and family member who I know in or who at one point lived in Venezuela has either been robbed, assaulted, kidnapped, shot, or murdered.” Very sad indeed. I agree with the author. This story needs to be told and people need to mobilize everywhere and change this.