Brain Researchers Say It’s Good to Zone Out

Have you ever found yourself driving on the highway for a long stretch of time, like say on a long trip, and just zone out? This happens to me all the time. I start off hyper-vigilant, paying attention to every little thing. But after a while I get in a groove and my thoughts drift off to other matters. Non-driving matters. I might ponder some task at work I could have done better, or where to go on my next vacation, or what happens if Brady ever retires.

Twenty or thirty minutes pass and I’m crossing a state border with no clue how I got there. Somehow I’ve drifted off into the netherworld of my own weirdo thoughts and yet still safely piloted a large metal object a pretty far distance at a pretty fast speed. How is this even possible?

Researchers in the field of neuroscience are, thankfully, looking into it. At a conference recently I learned that serious scientific research is underway on the seemingly unserious topic of mind-wandering. It is a fascinating field because it’s something that happens to all of us. Who among us has gone to a meeting or a required training and paid complete 100% attention the whole time? Few if any I would guess. We all experience this phenomenon, whether we call it mind-wandering, daydreaming, zoning out, etc. But because it is seen as a weakness in our culture, a failure of attention, it was not studied as a brain function until recently.

Yet for every moment where a man-child frets over the Patriots roster while driving, there can be the “eureka” moments where Einstein invents the Theory of Relativity while zoning out at his desk job in the Swiss Patent Office. Brilliant insights that come “out of the blue” are also functions of mind-wandering, and are certainly worthy of scientific study.

One the leading experts in this field is Dr. Kalina Christoff of the University of British Columbia. Her studies show that a mind-wandering brain is not undisciplined or somehow flawed. In fact, the neural activity observed during episodes of mind-wandering is more complex than expected, demonstrating an elaborate dexterity in human brains. Christoff states “the mind may be most active when it is freely wandering outside the confines of particular tasks or goals”.

At this point, I must concede that most of the science discussed by Christoff and other experts in this field is a way over my head. But I will try to describe in ordinary layperson’s terms what I’ve gleaned so far from the abstracts and summaries of articles I have read (tried to read, daydreamed while reading).

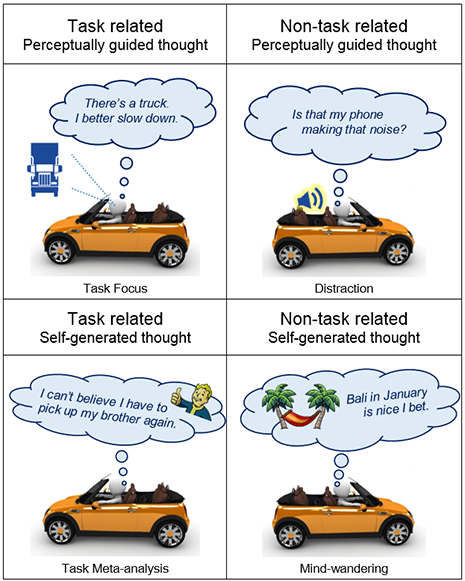

First, neuroscientists studying mind-wandering needed to define some basic terms. They have devised a commonly accepted framework that describes various types of mental attention. One parameter is the origin or motivation for a thought to occur. These origins are divided into 2 categories:

- Perceptually guided thought – generated by external sensory events and circumstances

- Self-generated thought – generated internally, spontaneously, without external motivation

The core of what these neurologists study is self-generated thought. But not all self-generated thought is considered to be mind-wandering. Thoughts are further defined by a second parameter: task-orientation, or what you are in the middle of doing when the thought occurs.

Thoughts are therefore classified in this framework as 1 of 4 types. In the chart below, I’ve used my highway driving scenario as an example:

Thought Classification Framework

This is a fascinating way to think about our minds and what they are doing at any given moment. Here we see that the wandering mind is not simply the task-focused mind “turned off”. There are 2 other in-between states, distraction and task meta-analysis. True mind-wandering only takes place when a self-generated thought, unrelated to task at hand, pops into your head.

Prof. Christoff and her colleagues study brain activity in each of these 4 scenarios. And they are learning what makes the mind-wandering phenomenon unique. Although research is ongoing, they do have an understanding of how I can envision my hypothetical Bali vacation for 20 straight minutes and not crash the car.

Brain activity happens not in any 1 isolated region of the brain, but across neural networks connecting several parts. The 2 key networks involved in mind-wandering research are:

- Executive network – active when the brain is engaged in problem solving or decision-making

- Default network – active when your brain is at rest, it maintains basic functions like breathing

Before anyone studied this topic in detail, neuroscientists had assumed the executive network was flipped on during task performance and then flipped off during mind-wandering. At that point the default network would turn on, run the show, and off you go to Bali. But the revolutionary discovery made by Christoff and others is that both networks are actively engaged during periods of mind-wandering.

This dynamic presents a complex picture of what mind-wandering means to our lives. We are not just zoning out. We are simultaneously leaving the sensory input of the present moment, but still somehow engaged with it (not crashing the car). And while all that is happening, a more elusive, abstract form of thought generation is taking place. This is Einstein in the Swiss Patent Office, Archimedes in the bathtub, and less dramatically, me in my car dreaming of Bali. Visions are conjured, problems are solved, all without the external world demanding it of us. Researchers see this mode of thought as an important source of creativity and innovation.

For me, the results of this research have many key implications. Understanding that a wandering mind can be a positive and not a negative force is a real breakthrough. As a trainer I have seen many students with that look in their eye that says they have checked out. Rather than viewing their zoned out space face as a failing on my part or their part, I now see it as an opportunity. There is a mind ready for creative endeavors, ready for creative challenges.

Additionally, I see these insights speaking to those of us who work with computers and IT systems. There can be a tendency to view our own brains as hard drives, to equate our human output with systems efficiency. But the research into mind-wandering clearly shows that the generation of our own thoughts is vastly more complex than we could imagine. We must take care to avoid a binary outlook on our own task performance. Who knows what great solution or innovation you might think of, if only you allow your mind the chance to wander.